Dis-ease (from old French and ultimately Latin) is literally the absence of ease or elbow room. The basic idea is of an impediment to free movement.

But nowadays the word is more commonly used without a hyphen to refer to a “disorder of structure or function in an animal or plant of such a degree as to produce or threaten to produce detectable illness or disorder”.

That is at least how the New Shorter Oxford Dictionary defines it, adding as synonyms: “(an) illness”, “(a) sickness”

Our understanding of health and illness has become increasingly more complex in the modern world, as we are able to use medicine not only to fight disease but to control other aspects of our bodies, whether mood, blood pressure, or cholesterol.

Health and disease are critical concepts in bioethics with far-reaching social and political implications.

Doctors are called on to deal with many states of affairs, and not all of them, on any theory, are diseases. A doctor who prescribes contraceptives or performs an abortion is not treating a disease. Although some women cannot risk pregnancy or childbirth for health reasons, women typically use contraception or abortion in the service of autonomy and control over their lives.

But, if we try to define health as simply the absence of disease or infirmity it leads us into difficulties: poor health can’t be defined simply in terms of disease because people can have a disease (especially one with minor symptoms) without feeling ill, and they can have unwanted symptoms (nausea, faintness, headaches and so on) when no disease or disorder seems to be present.

Nor is the fact that a condition is unwanted enough to describe it as ill health: it may be the normal infirmity of old age for example; and again a condition’s abnormality is not enough either—a disability or deformity may be abnormal, but the person who has it may not be unhealthy; and much the same may apply to someone who has had an injury.

Everything that used to be a sin is now a disease.

So to say whether or not physical ill health is present is therefore, a complex combination of abnormal, unwanted or incapacitating states of a biological system.

And things get even more complicated when assessing mental ill health.

Abnormal states of mind may reflect minority, immoral or illegal desires which are not sick desires. On the other hand, a psychopath, for example, may neither regard his state as unwanted, nor experience it as incapacitating.

The problem, however, is not just that ill health can be difficult to pin down. It is also that we normally think of health as having a positive as well as a negative dimension.

But here again things are complicated. A positive feeling of wellbeing, for example, may not be enough. Nor is fitness sufficient: the kind of fitness sought in athletic training, indeed, is sometimes detrimental to physical health; and the desire to maximize physical fitness as an end in itself may become an unhealthy obsession.

Often, what is required is only a “minimalist” notion of fitness, age-related and geared to everyday activities.

“True” wellbeing, requires an “essential reference to some conception of the ‘good life’ for a human being” and “some conception of having a measure of control over one’s life, including its social and political dimensions”.

Those factors, as well as the complex negative side, have to be taken into account when we ask what “health” means.

But even when we have taken all these factors into account, we cannot quantify how healthy an individual is with any precision. That is not just because the sum is complex. It is also because the components include value judgments.

Valere, from which value derives, means to be in good health in Latin. Health is a way of tackling existence as one feels that one is not only possessor or bearer but also, if necessary, creator of value, establisher of vital norms.

Health and disease, like many other concepts, are neither purely scientific nor exclusively a part of common sense. They have a home in both scientific theories and everyday thought.

That raises a problem for any philosophical account.

Suppose we try to say what health and disease really amount to, from which it follows that the scientific concept should fit the facts about world. If the picture we end up with deviates too far from folk thought, should we worry?

Conceptions of health, like conceptions of disease, tend to go beyond the simple condition that one is biologically in some state. In the case of health, one view is that a healthy individual is just someone whose biology works as our theories say it should.

As with disease, however, most scholars who write about health add further conditions having to do with quality of life.

The tendency in recent philosophy has been to see disease concepts as involving empirical judgments about human physiology and normative judgments about human behavior or well-being.

But, the most important thing about health is one’s lived experience of one’s own body, and in particular, that one should not feel estranged or alienated from one’s body.

On this view then, to be healthy is not to correspond with some fixed norm, but to make the most of one’s life in whatever circumstances one finds oneself, including those which in terms of some fixed norms may seem severely impaired or unhealthy.

“To be in good health means being able to fall sick and recover”.

What truly characterizes health is the possibility of transcending the norm, which defines the momentary normal, the possibility of tolerating infractions of the habitual norm and instituting new norms in new situations.

Perhaps a more colloquial way of putting it is that health is not a matter of getting back from illness, but getting over and perhaps beyond it: a feeling of assurance in life to which no limit is fixed.

The determination of what health means for your body depends on your goal, your horizon, your energies, your drives, your errors, and above all on the ideals and phantasms of your soul.

Thus there are innumerable “healths” of the body; and … the more we put aside the dogma of ‘the equality of men’, the more must the concept of a normal health, along with a normal diet and the normal course of an illness be abandoned by our physicians.

Only then would the time have come to reflect on the health and sicknesses of the soul, and to find the peculiar virtue of each man in the health of his soul: in one person’s case this health could, of course, look like the opposite of health in another person.

The long-standing biomedical model of disease has dominated medical practice because it has been seen to work. It is based on a technically powerful science that has made a massive contribution to key areas of health (for example, vaccination). The anatomical and neurophysiological structures of the body have been mapped out, and the genetic mapping of the body is being undertaken through the Human Genome Project.

The search for the fundamental – that is, genetic – basis of human pathology is on, whether the target is cancer, AIDS or Alzheimer’s disease. This ever closer and more sophisticated inspection of the body – or the medical gaze – has brought considerable power and prestige to the medical profession.

It has also established a large and profitable market for major pharmaceutical companies such as GlaxoSmithKline, Zeneca and Merck. The biomedical model also underlies the official definition of health and disease adopted by state and international authorities. National governments and international agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) proclaim their long-term health goal to be the eradication of disease.

So, the rational application of medical science is therefore a hallmark of modernity.

In as much as it has depended on the development over the past two centuries of a powerful, experimentally based medical analysis of the structure and function of the body and the agents that attack or weaken it.

However, during the course of this, scientific medicine has effectively displaced folk or lay medicine.

Modernity is about expertise, not tradition; about critical inspection, not folk beliefs; about control through scientific and technical regulation of the body, not customs and mistaken notions of healing.

This application of ‘rational medicine’ has also reduced reliance on patients’ own account of their illness.

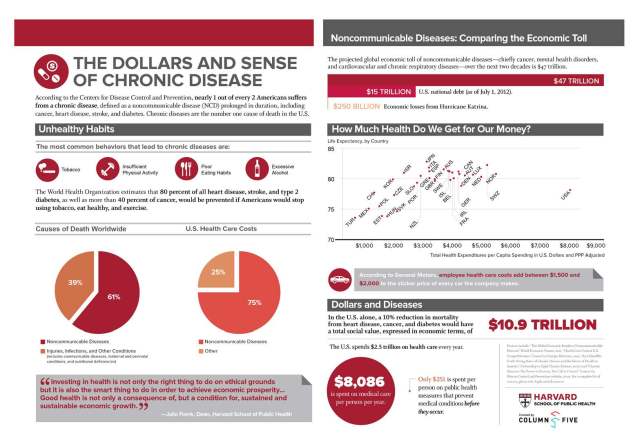

At the start of this century, 40 out of 100 patients died of acute illnesses. In 1980 these constituted only 1% of the causes of mortality. The proportion of those who die of chronic illnesses, on the other hand, rose in the same period from 46 to over 80%.

Health has received less philosophical attention than disease.

The desire to understand mental illness simply paralleled the success achieved by science in explaining physical illness. This in turn had followed a long period of stagnation in terms of developing a model that could both explain and prognosticate about illness with any degree of confidence.

Since then medical research has focused on extending disease nosography and understanding causal links between physiology, pathology, disease and illness.

Although this approach has been spectacularly successful in explaining and controlling a wide range of illnesses, particularly those involving pathogens and other external agents, it has been much less successful in dealing with chronic illnesses linked to the failure to adapt appropriately to physiological stresses due to ageing, immune reactions and environmental insults, including social, physical and psychological factors.

Clearly health care is failing to deal with the nation’s health problems, though whether this is due to inherent failings in the system or the fact of being overwhelmed by demand is not clear.

Whichever it is, and it may well be both, it is time to re-examine some of the fundamental assumptions on which Western health care is based, namely the concepts of health, illness and disease themselves.

The power and status of the medical profession and the health industry in general should not deflect us from asking about the social basis of health and illness.

People’s perception of health and illness is culturally variable, highly context-specific, dynamic and subject to change. Crucially, there is no clear-cut relationship between the existence of a physical or emotional feeling and the judgment that this indicates illness (that it is a ‘symptom’), requiring consultation with a doctor and becoming a patient.

“A medical man”, needs three things. He must be honest, he must be dogmatic and he must be kind”. A philosopher, by contrast, needs only the first of these.

When we’re ill, we’re ill.

The problem is that it is not clear that health, illness and disease are purely biological issues.

It’s not just the fact that biological approaches to chronic illness have not produced the anticipated benefits. It is now well accepted that psychosocial factors play a major part, not just in the experience of illness, but also in the development of disease. (Engel first proposed this idea in his classic paper of 1977)

To say that health and illness have a social basis may at first seem to be an example of sociological arrogance, claiming for ‘the social’ more than can be credibly accepted.

Perhaps because we tend to assume that a modern scientific or “objective” picture of the world, in which we ourselves figure as natural phenomena, is the “true” view of the “real” world?

In this scientific picture, it is difficult not to see something like the image of the athlete as the ideal of health—for which all that comes before is a preparation, and all that follows a process of disintegration and decay.

But there is a serious problem about taking this objective scientific picture as the “true” view of the “real” world. The physicist Schrödinger put it as follows.

The only way scientists can “master the infinitely intricate problem of nature”, is to simplify it by removing part of the problem from the picture. The part that scientists remove is themselves as conscious knowing subjects.

Everything else, including the scientists’ own bodies as well as those of other people, remains in the scientific picture, open to scientific investigation. This “objective” picture is then taken for granted as “the ‘real world’ around us”; and because it includes other people who are conscious knowing subjects just as the scientist is, it is difficult for the scientist to resist the conclusion that the “true” picture of the “real world” must be an “objective” picture, which includes the conscious knowing subject as another object. Whew!

That conclusion, however, fails to fit all the facts. For, as Schrödinger says, this “moderately satisfying [scientific] picture of the world has only been reached at the high price of taking ourselves out of the picture, stepping back into the role of a non-concerned observer”.

The problem about conceiving health in terms of fixed norms such as those of biochemistry, or the ideal of the athlete, is that it assumes that the objective observer’s viewpoint is the true one, and discourages those who adopt it from seeing themselves as actors or agents, rather than patients who are acted upon.

If we want to gain a more adequate understanding of the meaning of “health”, we may have to be prepared to offload rather less, and take responsibility for rather more, of our minds.

Religion has always tried to “round off” or “close the disconcerting‘openness’” of human experience. In the past, it has done this, often very successfully, in terms of scientific or pre-scientific ideas which at the time seemed plausible to everyone.

But, when these ideas were overtaken by new scientific explanations which seemed to fit the facts better, religion, being more conservative than science, was slow to give them up; and this helped to create the impression among many people that it was only a matter of time before science would explain everything.

But, this idea of science demonstrating “a self-contained world to which God” (or the religious or transcendent dimension) is “a gratuitous embellishment”. If science were able to exclude the religious or transcendent dimension from reality (rather than just from the scientific picture of reality), it would be at the cost of excluding the first-person human dimension also.

And, the idea that science can do this, springs not “from people knowing too much—but from people believing that they know a great deal more than they do.

Our doctors may explain our symptoms in terms of the liver’s lost capacity, but if that lost capacity doesn’t impinge on our life, maybe we wouldn’t consider it necessary to have it corrected.

Modern medicine only offers a biological explanation based on bio-mechanisms. While these kinds of explanation are useful in dealing with specific ranges of conditions, they are proving less effective in dealing with many of the chronic illnesses currently afflicting human beings.

Without major progress in overcoming the body/mind problem, this remains a key hurdle for the biological medical model. Until now the problem has been sidestepped by ‘bolting on’ psychosocial elements as causal or risk factors to the more central biological explanations.

But, wholeness and healing—are intimately related.

Healing as understood by religion not only is the natural process of tissue regeneration sometimes assisted by medical means, but also as whatever process results in the experience of greater wholeness of the human spirit.

“A physically dependent patient who has come to terms with his past life and his approaching death, for example, may well feel, and thus (because no one else is better placed to judge) be nearer to ‘wholeness’ than ever before.”

Such a person may even, in this perspective, be described as “healthy”.

The disconcerting openness of experience raises a question mark against the conventional wisdom.

Perhaps a more critical stance would be to admit ignorance without denying admission to hope?

Live and Learn. We All Do.

Thanks for reading. Please share 🙂

Please don’t forget to leave a comment.